Photos by Fred Dott

Performance by Sara Ezzell and Lisa Torres Luna

Das Projekt wird freundlich gefördert durch die Behörde für Kultur und Medien der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, die Hamburgische Kulturstiftung sowie die Liebelt-Stiftung, Hamburg.

THE WEAK LIPS OF A WOMAN

Cordula Ditz’s installation THE WEAK LIPS OF A WOMAN is an exploration of the intersections between Spiritualism, early feminism, and radical social movements. The title is derived from a quote by Lizzie Doten, a medium who recited poetry under the influence of the spirit of Edgar Allan Poe. Within the spiritualist religion, women were not regarded as weak; rather, their supposed fragility and sensitivity were seen as strengths, enabling them to connect with spirits. The installation comprises video, sound, paintings, and sculptural elements.

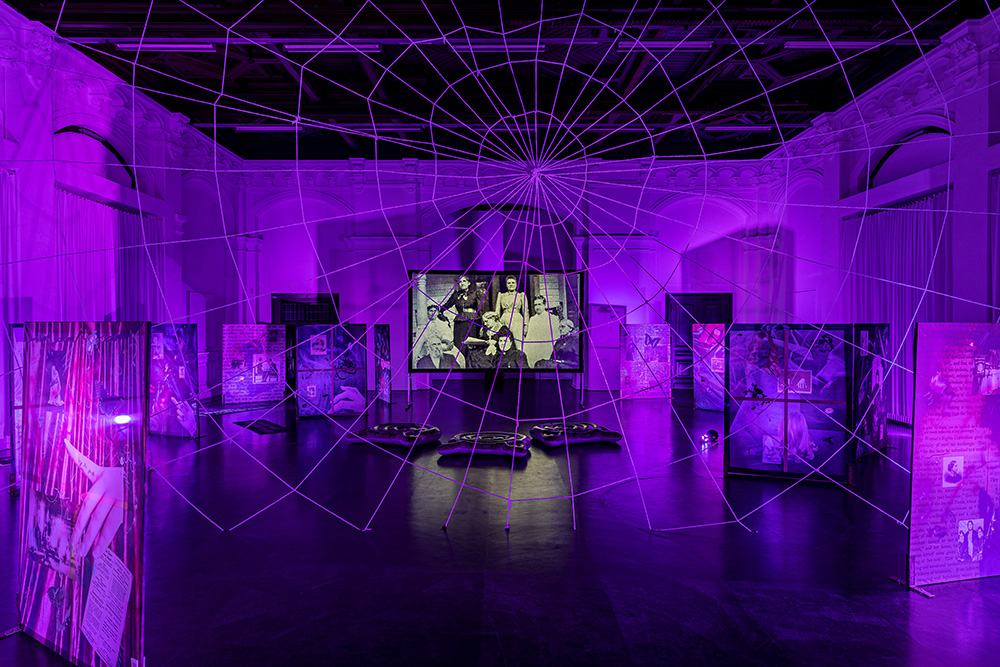

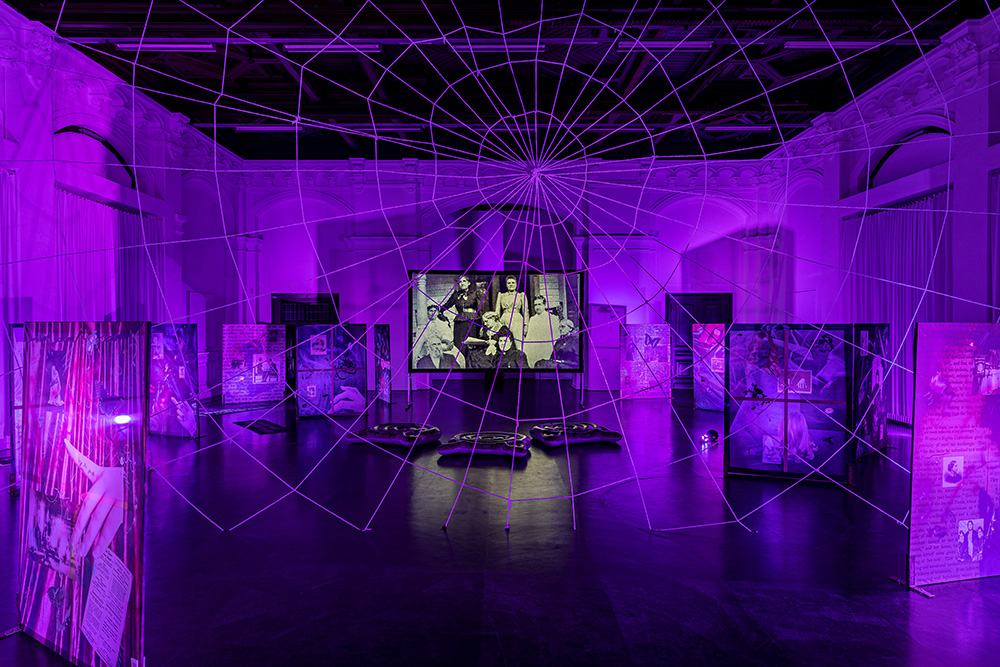

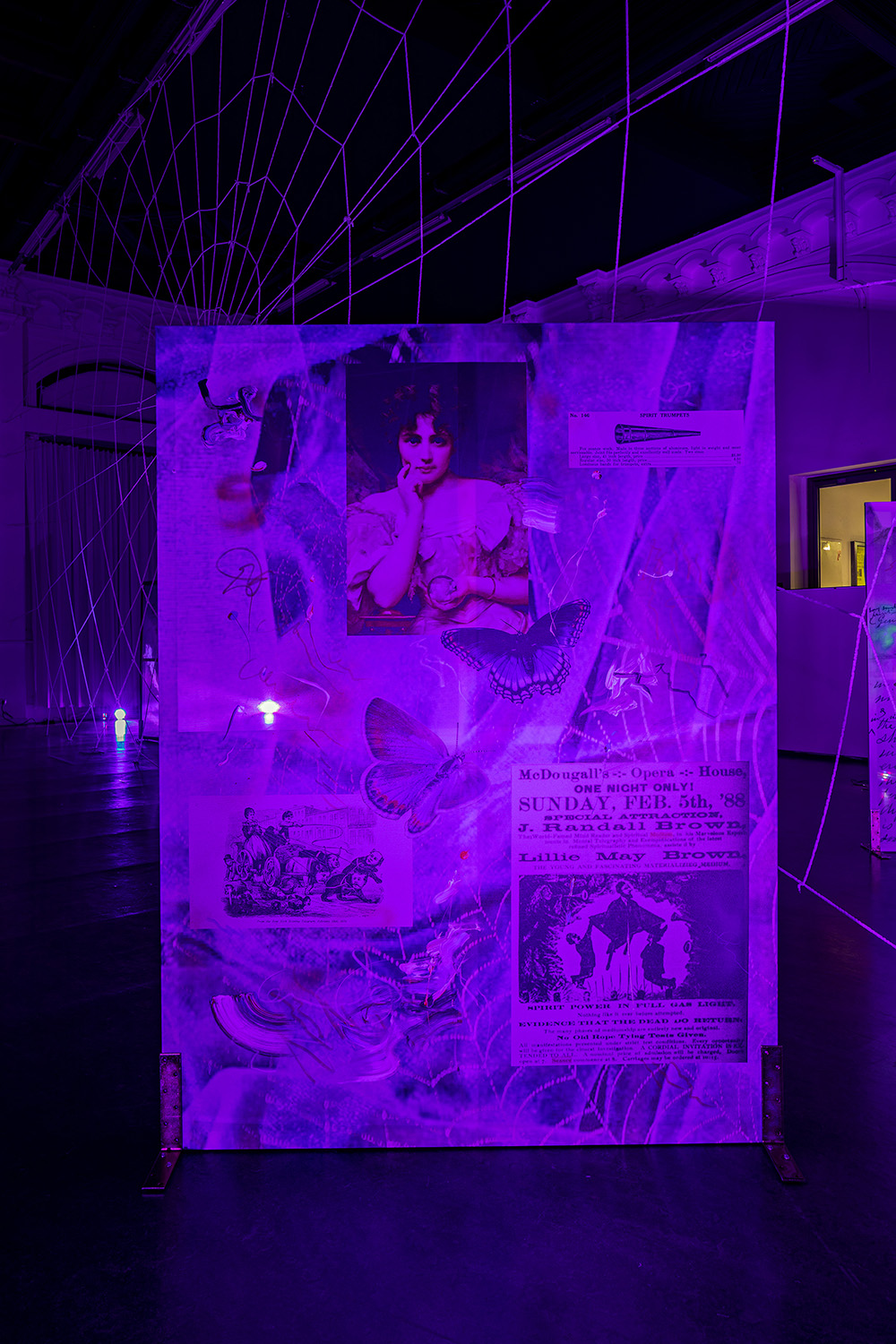

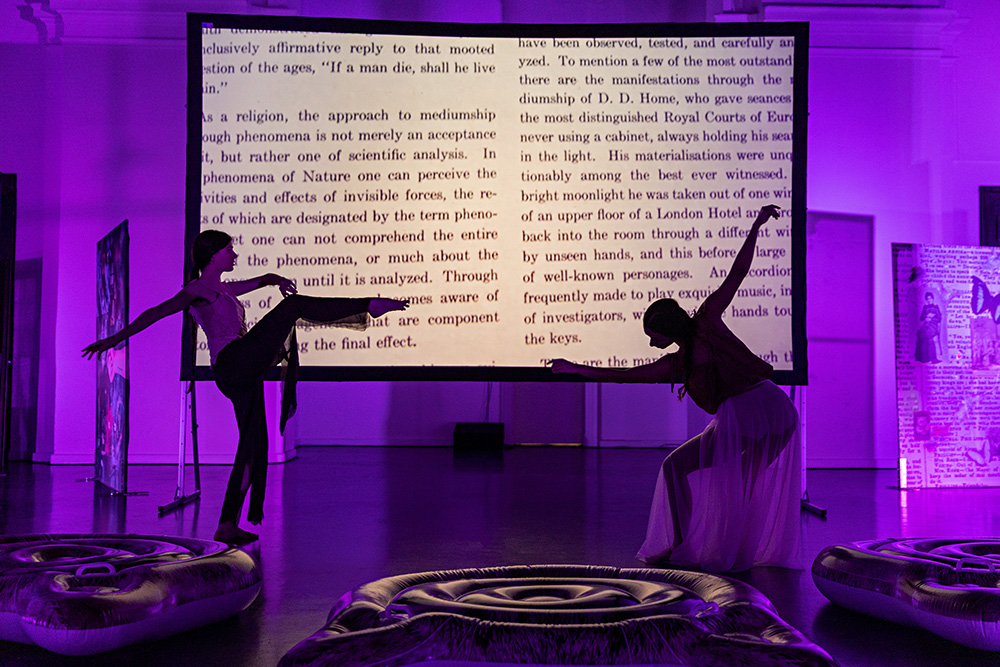

Behind a massive spiderweb-like structure that spans the entire length between the floor and ceiling, dividing the room, the video is positioned. The web introduces a physical and metaphorical barrier, inviting viewers to contemplate the boundaries between visible and invisible, tangible and intangible, past and present. The space is bathed in theatrical lighting, predominantly in violet tones, which enhances the unreal mystical atmosphere of the room. The video features archival material interspersed with scenes shot in the spiritualist community of Lily Dale.

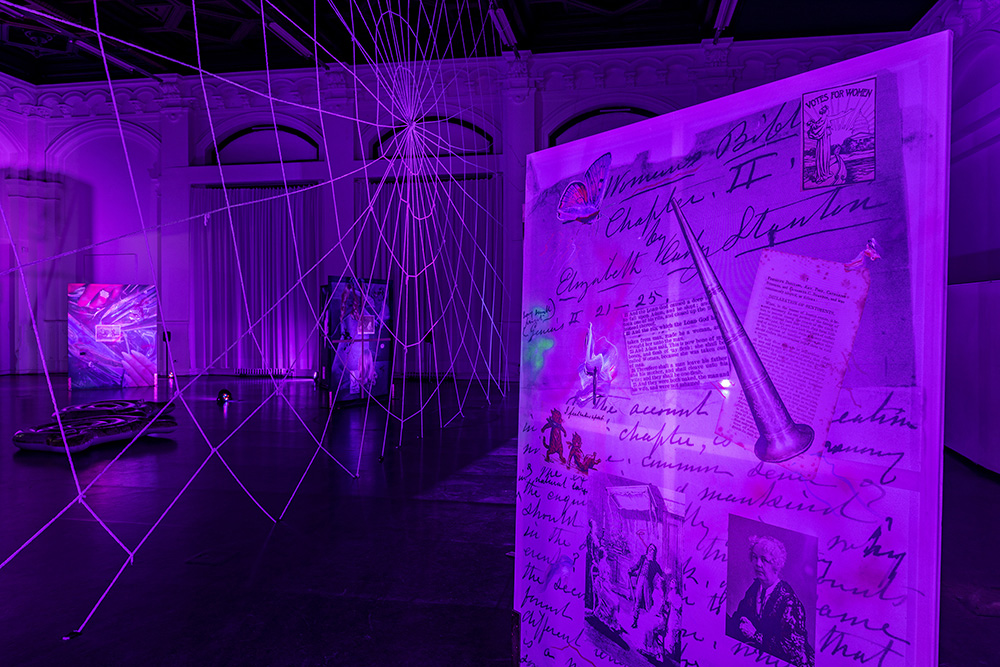

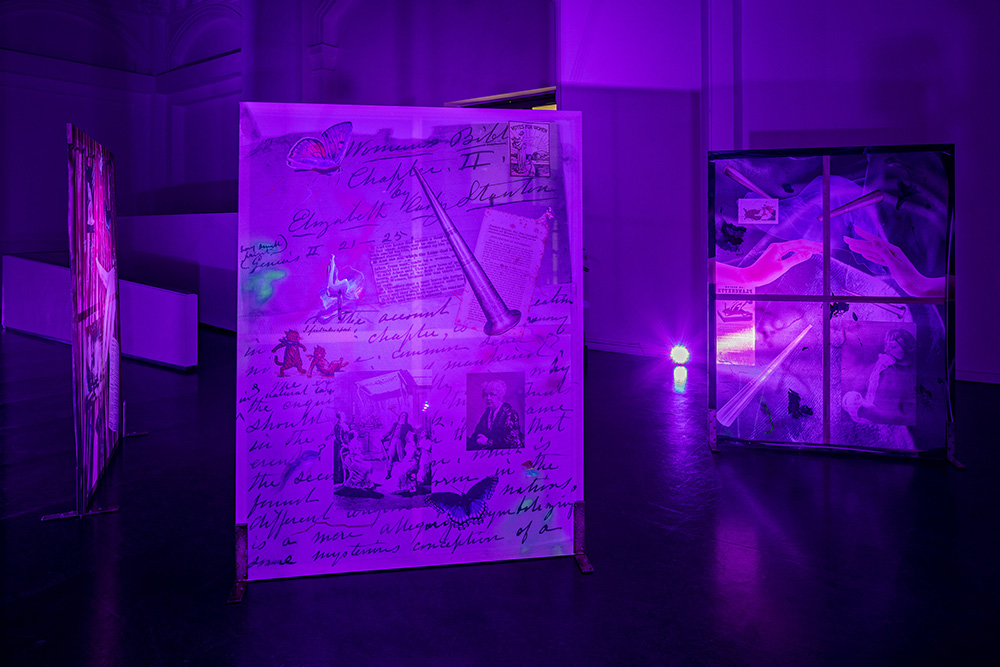

Several paintings stand throughout the room, adding a another layer to the installation. These paintings, rendered on flag fabric printed with historical collages, echo and expand the themes of the video. Slightly transparent, the paintings allow viewers to look through them, merging the layers of history and personal reflection into a singular plane.

On the floor, printed yoga mats bear quotations that contribute to the reflective atmosphere, extending an invitation to the audience to engage with the installation‘s physical dimension. The quotes, which are related to women’s rights, include statements such as “Deeds not words” by the political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, “Revolution is not a one-time event” by feminist poet Audre Lorde, and “The more we see, the more we are capable of seeing” by the 19th-century astronomer Maria Mitchell. These quotes further emphasize the feminist themes of the work.

The spiderweb structure, which serves as a fundamental symbol in the installation, plays a crucial role by underscoring themes of interconnection, resilience, and transformation. In both feminist and spiritual contexts, spider webs are powerful symbols of creation and agency, reflecting the ability to weave one’s own path and reshape narratives. The sacred writings of ancient India record that a large spider created the universe, weaving a web from her glands and sitting at its center, directing its motion. The earth, in this context, is conceptualized as an integral element of the web, and the spider, in her agency, has the capacity to decide whether or not to consume her creation, a practice that many spiders engage in. This act of creation and destruction, akin to the cycle of birth and death, is a metaphor for the ability to clear a new path and weave a new universe. Spider webs, furthermore, evoke a duality: they are both beautiful and fragile, yet strong enough to trap prey, thereby symbolizing the interplay of vulnera- bility and resilience.

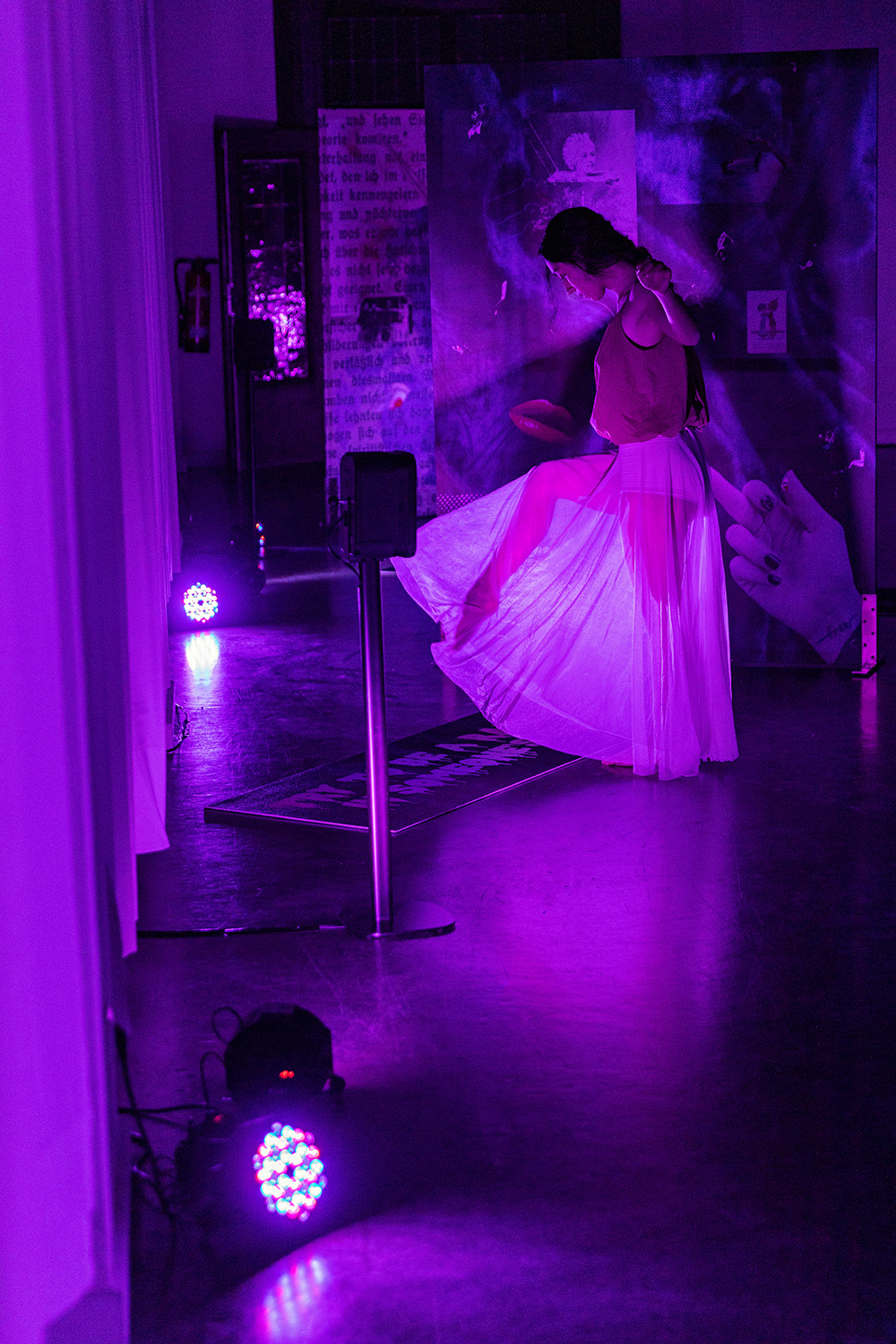

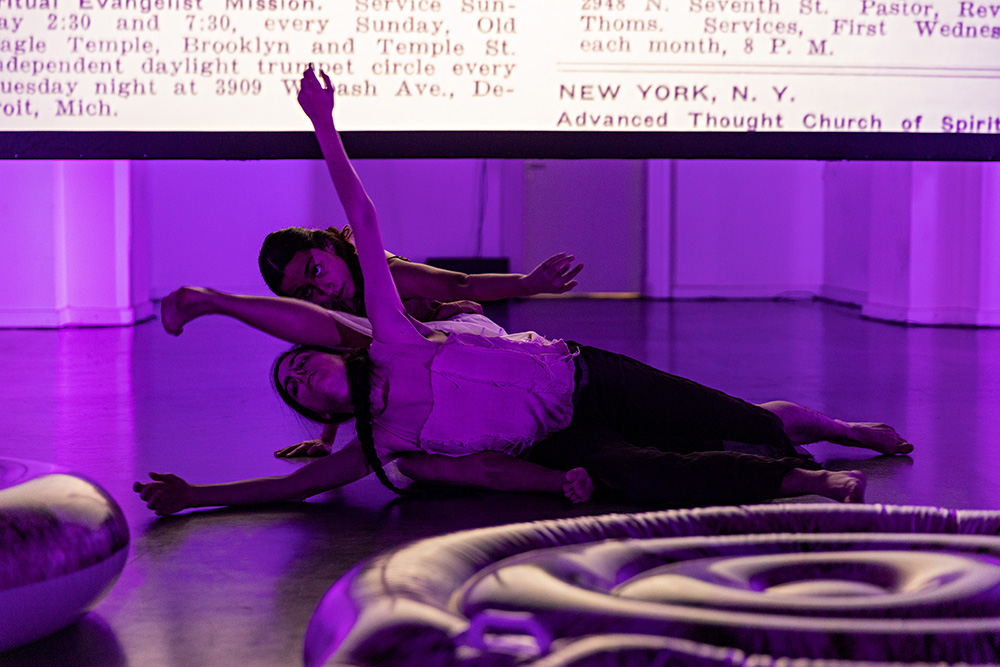

THE WEAK LIPS OF A WOMAN further incorporates trauma yoga sessions, durational dance performances, and a talk by photographer and author Shannon Taggart, thereby deepening the engagement with the historical and thematic context of the work. The durational dance performances, each lasting four hours, featured two ballet-trained performers. Through improvisation, the dancers sought to render the unseen energies in the room visible, creating a mesmerizing interplay between movement, space, and the intangible forces evoked by the installation. By making these energies visible, the dancers draw a line between the process of abstract painting—which is also often based on invisible energies—and the philosophical aspects of a religion that believes in the continuity of life in the form of spirits accompanying us. This juxtaposition highlights the shared act of revealing the unseen, whether through art or faith, and asks viewers to consider how these invisible forces shape human experience.

The act of visualizing the intangible extends the installation’s thematic depth, encouraging reflection on the manner in which Spiritualism and abstract art both function as conduits for exploring the realm that lies beyond immediate perception. Ditz seems to suggest that art and faith are not separate but intertwined practices that allow us to navigate the mysteries of existence,

memory, and connection. The performance fosters a heightened awareness of the ways in which we interpret and interact with the unseen forces that govern our lives, blending physical movement with metaphysical inquiry.

The trauma-sensitive yoga sessions, which take place in a smaller room at the rear of the exhibition space, invite visitors to participate. This intimate space continues the dialogue between the somatic, emotional, and historical themes of the installation. In addition to the paintings and yoga mats, the room features an inflatable unicorn skeleton with a rainbow-colored mane, a whimsical and surreal element that lightens the atmosphere while subtly reinforcing the installation‘s themes of transformation and duality. The sessions, held by a dancer, prior to the exhibition‘s official hours, aimed to create a safe and reflective space for participants. During standard operating hours, visitors are invited to sit on one of the yoga mats and listen to a guided meditation, providing an opportunity for stillness and personal reflection.

This room serves as both a refuge and a continuation of the larger work’s exploration of invisible energies and healing. The inflat- able unicorn skeleton, with its playful yet eerie appearance, adds a layer of surreal humor and invites reflection on the intersection of life, death, and rebirth. This combination of lightheartedness and depth mirrors the overarching themes of the installation: the coexistence of vulnerability and strength, playfulness and seriousness, past and present.

The installation is founded on intensive research into the origins and development of Spiritualism, particularly its profound connection to early feminism in the United States. Spiritualism began in 1848, in the same region of New York State and during the same year as the Seneca Falls Convention, which marked the birth of the organized women’s rights movement. This movement

uniquely allowed women to discard societal limitations without challenging ideas about women’s nature, providing an unexpected platform for empowerment. In contrast to the prevailing religious groups of the time, which reinforced traditional hierarchies of gender, race, and class, Spiritualism represented a radical departure. It aligned itself not only with women’s rights but also with abolitionism and other progressive movements, influencing suffragist leaders like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott or Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for U.S. president. Beginning in 1891, Susan B. Anthony herself delivered speeches at Lily Dale, deeply impressed by the women of the Spiritualism movement who practiced mediumship.

One painting, titled I FEEL RATHER UPSET, features the original manuscript of the “Woman’s Bible”, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton, a leader of the women’s rights movement, scrutinized the Bible from a woman’s perspective and her radical views on religion led to her abandonment by the movement she had helped build. When the program for the 75th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention was created, Stanton was omitted, despite her being the primary force behind the event. Other parts of the collage reference the Fox sisters, who sparked modern Spiritualism and the Declaration of Sentiments. The digitally printed collages are overpainted with acrylic, oil stick, and spray paint. The collages incorporate emotive brushstrokes, adding layers of the subconscious and the emotional to the works. The utilization of these backgrounds, which are woven with their own web of stories and connections, opens up conceptual spaces that invite viewers to meander through history and time.

At a time when women were considered the property of their husbands or fathers, Spiritualism granted women equal authority, opportunity, and participation. Women in the movement often held high religious offices and became public figures, speaking before large, mixed-sex audiences. These mediums would deliver trance lectures under the supposed influence of spirits, becoming the first group of American women to speak publicly in such a context. The nervousness and fragility of women, qualities otherwise stigmatized in Victorian society, were reframed within Spiritualism as assets.

It was believed that women’s perceived weakness made them more receptive to spiritual messages. Female mediums were thought to be uniquely capable of receiving messages from male spirits, a role that men could not fulfill, as they were believed to only channel female spirits. This belief created a paradoxical space where women could serve as conduits for male spirits, granting them public visibility. This practice subverted societal norms by reducing women to mere vessels for the spirits, absolving them of accountability for their radical or political statements.

Through THE WEAK LIPS OF A WOMAN, Ditz examines the paradoxes of a movement that both empowered and objectified women. By providing women with a platform to publicly speak and challenge societal norms, Spiritualism fostered an early form of feminist activism, all while operating within the confines of traditional gender roles. The broader cultural context, in which reason and spirituality coexisted, underscores the innovative yet contradictory nature of this movement. During this period of technological innovation, including the invention of the telegraph and experimentation with electricity, prominent scientists such as Marie Curie attended séances, and figures like Thomas Edison sought to develop devices to communicate with spirits. This historical openness to Spiritualism underscores its significant cultural influence and its radical potential to reshape ideas of gender and power. Furthermore, by examining Spiritualism as a Utopian model of religion, which does not discriminate between the sexes, and by highlighting its historical alignment with radical reforms, the installation explores and emphasizes the intricate relationship between gender, power, and agency. The layered installation invites viewers to navigate its historical, physical, and metaphysical dimensions, challenging them to reflect on our perception and discover the ways in which historical narratives shape our present understanding of gender and equality.